Ressources dossier

AgroecologyAI for plant and animal health

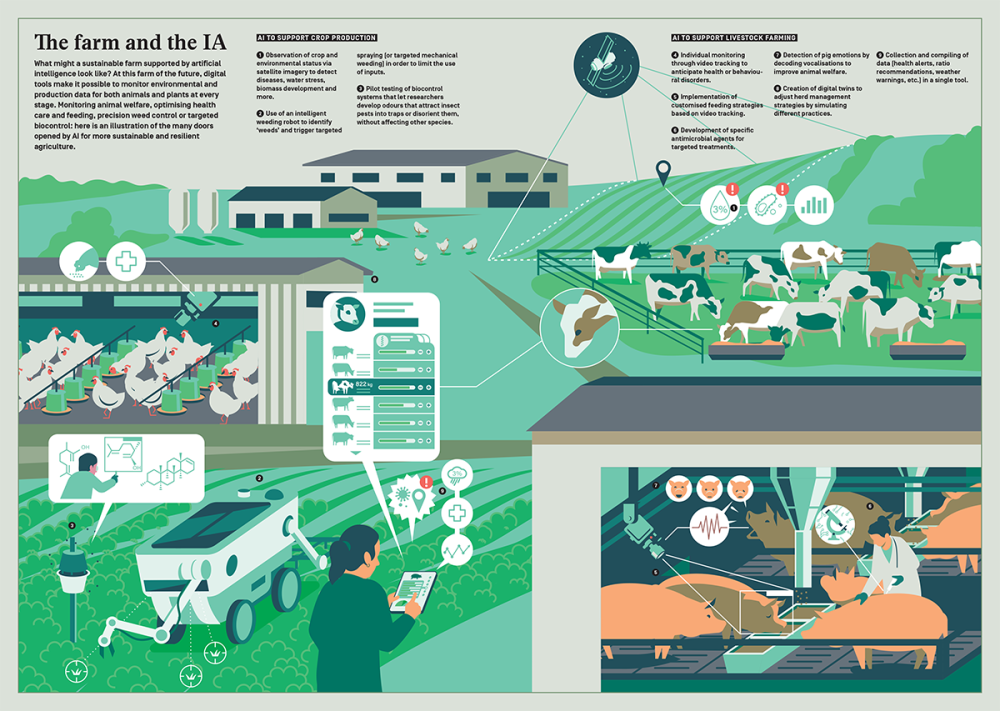

From predictive systems designed to better manage plant and animal health to the identification of new biocontrol agents, what are the next stages in the development of AI to support plant health, animal health and animal welfare?

Published on 11 February 2026

‘The earlier, the better!’ This maxim, which guides the field of epidemiology, takes on its full meaning with AI. In agriculture, AI will play an increasingly crucial role in the early detection and effective control of pests and diseases. By providing advanced tools to detect, anticipate and manage pests and pathogens (crop insect pests, viruses, bacteria and phytopathogenic fungi), digital technologies—and AI in particular—are enabling research to move towards more predictive health monitoring.

Click on the image to download the file.

Real-time monitoring

In crop production, AI underpins numerous developments in diagnostics based on imaging and molecular data (DNA sequences), facilitating the early detection and automated monitoring of pests and diseases across large geographical scales. AI algorithms analyse images of crops to identify subtle symptoms of infection and/or the presence of low pest densities, enabling rapid intervention. ‘These technologies provide real-time monitoring that is earlier and more spatially targeted, which is essential for effective management of plant pests and diseases, in line with the objective of sustainable, resilient agriculture that relies less on pesticides,’ explains Arnaud Estoup, an INRAE researcher at the Centre for Biology and Management of Populations (CBGP).

‘These technologies provide real-time monitoring that is earlier and more spatially targeted, which is essential for effective management of plant pests and diseases.’

Arnaud Estoup

Researcher Samuel Soubeyrand confirms that AI can be decisive in detecting certain bacteria such as Xylella fastidiosa, which causes a lethal disease affecting grapevine, olive trees, citrus and other crops. ‘Using autonomous drones guided by AI, and by continuously feeding data back into the system, effective precision scanning could be used to monitor the health status of crops across a farm and its surrounding environment and identify disease at extremely early stages,’ he explains. In the case of X. fastidiosa, such ultra-early detection would be game changer, as infected plants must be uprooted as soon as possible to prevent the spread of the bacterium. Some experiments have shown that drones equipped with hyperspectral sensors can identify this disease earlier than molecular tests, which currently serve as the diagnostic reference standard.

Detecting early warning signs

AI harnesses vast and heterogeneous datasets to anticipate threats to the health of living organisms. The Beyond project, coordinated by INRAE researchers Cindy Morris and Samuel Soubeyrand, is largely dedicated to exploring this approach in order to produce, through machine learning, plant health risk indicators that can be used by field practitioners and public policymakers. Among the approaches developed, natural language processing (NLP) tools such as AlvisNLP help analyse, as automatically as possible, an immense corpus of texts written in several dozen languages and available on the internet (official announcements, media, scientific articles, grey literature, etc.).

The Plant Health Epidemiological Surveillance Platform (ESV), which contributes to the project, uses this approach to identify the earliest signs of increasing threats to national agricultural production caused by pests and pathogens identified as priorities. In the longer term, this approach could be transferred to private or public organisations tasked with monitoring web-derived textual data, across various application fields related to health, the environment, the economy and beyond.

AI also contributes to the democratisation of plant knowledge, both for farmers and for the general public. The Pl@ntNet platform and mobile application are an excellent example produced by public research (see p. 82).

Predicting new invasive species

In the future, AI’s contribution to plant epidemiology will extend beyond its early warning function. ‘AI will also enable researchers to refine risk assessments by characterising the genomes of introduced pests and pathogens,’ explains Arnaud Estoup. The risk that a species will establish and spread depends, at least in part, on the genetic make-up of the introduced individuals. Data on genomic diversity and environmental characteristics can be used to detect genetic variations that influence adaptation to local conditions. This makes it possible to predict which genetic traits increase or decrease a population’s ability to establish itself in a given environment.

This approach, known as genomic offset, compares the genetic make-up of a given population with one that would allow pests to effectively adapt to a new environment. Until now, it has been used to predict how populations might respond to climate change, but it may also help anticipate the risks associated with the introduction of pests and pathogens into new areas. These predictions rely on machine learning algorithms developed within a highly transdisciplinary project with strong INRAE involvement, conducted as part of the PEPR Mathematics in Interaction programme (coordinated by CNRS) and which include recent advances in AI.

In agroecology and biocontrol, this new technology could soon make a major leap forward by identifying which parasitoids —insects that are natural enemies of other insects— would be most effective in controlling newly introduced exotic insect pests (referred to as invasive species). ‘Until now, we would go back to the pest’s region of origin to find its parasitoid and then import it. With AI, we will be able to determine whether a potential natural enemy already exists locally using databases —training datasets— to synthesise a large number of biological traits in both parasitoids and their associated hosts. These databases are built using text-based information extraction using AI algorithms, notably LLMs (Large Language Models), and/or through the production of ad hoc data,’ explains Arnaud Estoup.

Among the top-priority targets for these future predictions are the 100 exotic pests posing the greatest threat to Europe. An INRAE-coordinated project under the Écophyto plan, together with a project for the Agroecology and Digital Technology PEPR programme (coordinated by INRAE and Inria as part of France 2030), mobilise AI-based image recognition to optimise natural pest regulation in perennial Mediterranean crops such as olive and citrus. Also developed are LLM tools to predict parasitoid–host relationships. The Écophyto plan project also involves the Montpellier-based AI start-up BionomeeX, the interprofessional organisation France Olive, and two INRAE teams: AGAP Corse and the CBGP joint research unit.

Identifying health disorders in animals quickly

Animal health and welfare are areas in which AI is expected to play an increasingly important role. ‘We are still in an experimental phase, but many projects demonstrate the great potential of AI, for example in continuously monitoring animals and detecting health disorders at an early stage,’ says Pauline Ezanno, Head of the INRAE Animal Health Division.

In the BIOEPAR unit, two projects supported by European funding and the Institut Carnot France Futur Élevage are developing Connect’BRD, a decision-support tool for managing respiratory diseases in young cattle obtained by combining several AI methods. Tested on nine farms, this tool couples AI-based processing of data from individual animal sensors with epidemiological models that are explicitly described, intelligible and adjustable thanks to AI. Connect’BRD identifies sick animals at a very early stage and helps farmers find the most appropriate interventions, limiting antibiotic use as a result.

The WAIT4 project, funded by the Agroecology and Digital Technology PEPR programme, mobilises AI and new technologies to assess the welfare of farm animals subject to agroecological transition related challenges. In ruminants, the objective is to automate real-time monitoring (via video, accelerometers or other connected sensors) and detect warning thresholds using AI. ‘We can detect negative or positive social interactions, thermal discomfort, diseases or lameness even before they manifest clinically,’ explains Florence Gondret, a researcher in the Pegase joint research unit.

Behaviour and vocalisations as indicators of welfare

Within the same unit, other research aims to assess animal welfare automatically with the help of AI, by designing detection and early-warning systems for farmers. Researcher Charlotte Gaillard is leading work on improving animal welfare, initiated through a PhD supported by #DigitAg, the Convergences Institute for Digital Agriculture. ‘Using cameras and video analysis from our sow feeding optimisation software, we are trying to determine automatically and continuously whether the animal is engaging in positive or negative interactions with its conspecifics—something that has so far been very little measured,’ the scientist explains.

The snout, neck and tail of each animal are annotated and their positions recorded. Every half-second, the software provides information on animal movements by tracking the coordinates of these points, their movement speed and the distance between individuals. ‘Based on this data, machine learning algorithms can accurately identify whether interaction occurs, whether the encounters are positive or negative, and finally the direction the interaction is taking,’ summarises the researcher. As the frequency of different types of interaction can be linked to the welfare status of each animal, this makes it possible to prevent or identify negative behaviour. For example, a negative encounter oriented from snout to tail may be associated with tail biting.

INRAE researcher Céline Tallet focuses on pig vocalisations. Pig emotions are traditionally analysed through their vocalisations using software that measures characteristics such as frequency, intensity and duration. This manually demanding method is now being replaced by an algorithm based on neural networks developed to automate emotion recognition. The algorithm can identify, with more than 90% accuracy, whether a vocalisation expresses a positive or negative emotion—outperforming traditional image-based methods (70-80%).

‘Even though AI reduces the need to observe animals directly, it is important not to replace human expertise.’

Céline Tallet

Work on the soundscape of livestock buildings has yet to be fully automated, as pig vocalisations must still be extracted from background noise. ‘Even though AI reduces the need to observe animals directly, it is important not to replace human expertise—that of researchers and farmers—in these projects, and to give due attention to the ethical and practical aspects of AI,’ Céline Tallet reminds us. For the WAIT4 project, she is working with Inria to develop a system that combines image and sound analysis to further optimise the recognition of the emotional states of pigs.

Biocontrol: Tricking an insect’s sense of smell using AI

AI plays a key role in the search for biocontrol solutions to eliminate insect pests in agriculture because it accelerates the discovery of new odorant molecules capable of influencing insect behaviour. When released into the air, these molecules mislead pest insects or attract them into traps —without affecting non-target species.

Two projects use this approach to study insect olfactory receptors, which are modelled and screened using AI to identify molecules capable of deceiving insects’ sense of smell. ‘As part of the Parsada programme, the ARDECO distributed chemical ecology infrastructure project will use established AI tools, while the InvORIA project of the EXPLOR’AE 2 programme will develop AI tools tailored to the unique structure of insect olfactory receptors with the objective of predicting more effectively which odorant molecules activate them,’ explains Emmanuelle Jacquin-Joly, an INRAE researcher at the Institute of Ecology and Environmental Sciences of Paris (iEES-Paris).

To learn more about the project, view the movie Biocontrôle des insectes ravageurs (4'54).

-

Anne-Lise Carlo

(Send email)

Author / Translated by Emma Norton and AI

-

Véronique Bellon-Maurel, Jean-Pierre Chanet, Claire Rogel-Gaillard

Scientific pilots