Ressources dossier

Climate change and risksPublic policy for private forests

Published on 09 December 2022

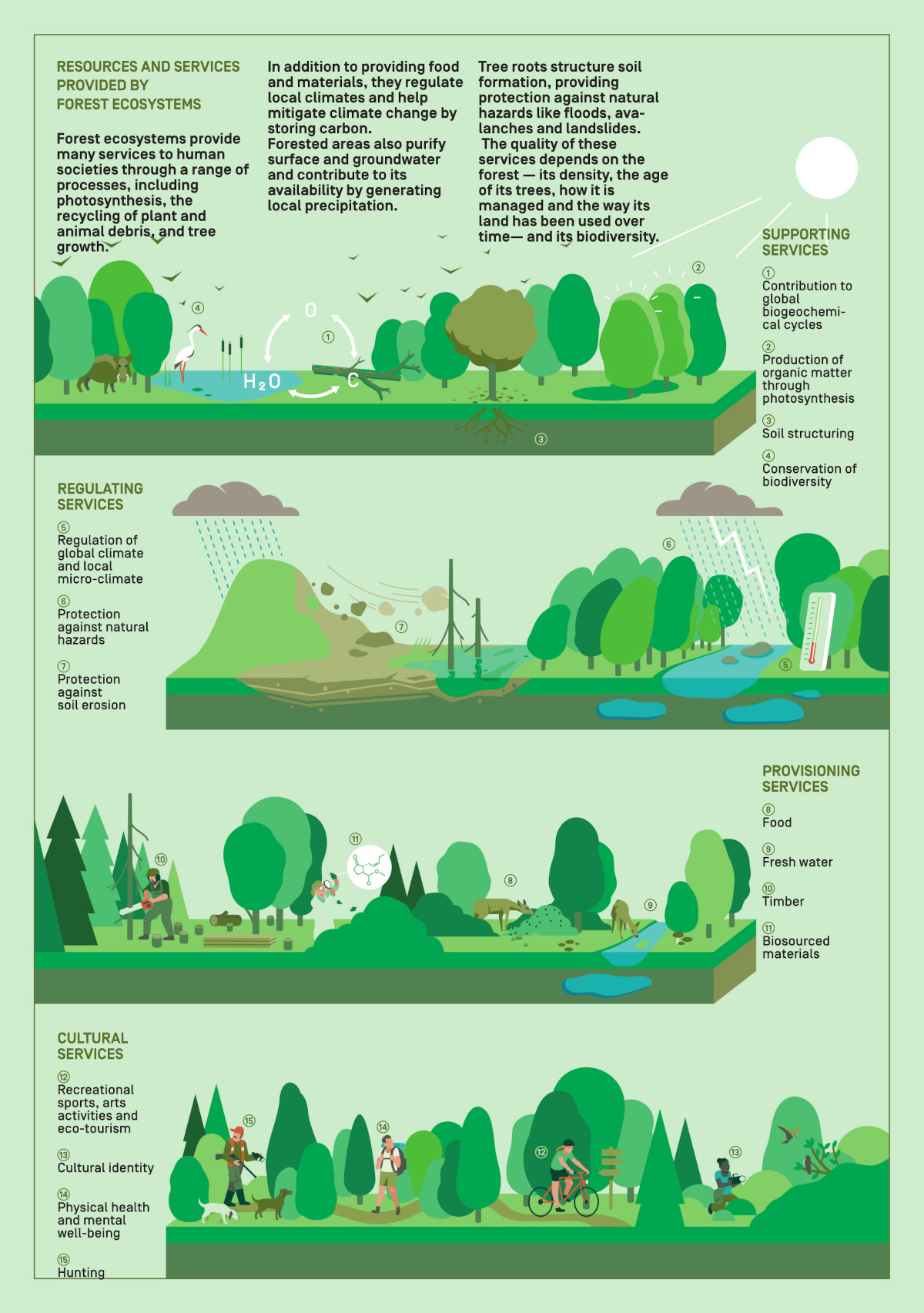

Climate change has made forests strategic again for States, as evidenced by France’s national low-carbon strategy (SNBC), its roadmap for the adaptation of French mainland forests to climate change drafted in 2020 by forest and timber stakeholders at the request of the French Ministry of Agriculture and Food, as well as the new European Union Forest Strategy for 2030. Guidance documents emphasise the need to strengthen carbon storage capacities by revitalising wood harvesting for long-term uses (timber frame construction, carpentry, flooring, etc.), while preserving ecosystem services. The roadmap lists operational initiatives to be implemented by 2050. How can owners meet these national challenges together?

Changing the pace of management to adjust to uncertainty

“Landowners are well aware of climate change, and some are already seeing its effects on their forests,” observes Julie Thomas, a socio-economist at the Centre national de la Propriété Forestière (CNPF), “but 84% of them have not adapted their silvicultural practices, nor plan to do so in the next five years. ” This is one of the findings of the MACCLIF survey, conducted between 2017 and 2019 with 922 forest-wood sector professionals and 960 owners. The survey studies their perceptions of climate change and identify obstacles to the adoption of new management practices. Why aren't things changing? “Many of them feel there isn’t enough information, or that it is contradictory. Their uncertainty pushes them to stick to familiar methods,” says Julie Thomas.

In contrast, 78% of public and private managers surveyed said they had already changed their forest management practices and the advice they give to owners, as well as their management plans. Some prefer more intensive forestry techniques and technology to deal with natural risks, such as choosing fast-growing species, shortening cycles with earlier and therefore more frequent cuts, and standardising the use of younger timber in production.

Others choose to make stands more resilient to hazards by accompanying natural processes like the diversification of species and preparation for regeneration under a mature stand. Philippe Deuffic, a sociologist at the ETTIS unit in Bordeaux, explains: “For the past 30 years, we have observed a growing importance of environmental considerations in forestry practices, driven by environmental organisations and the general public, but also by foresters who are interested in these issues. Certain practices are re-appearing that were previously considered economically costly and unproductive, such as conserving deciduous trees under a stand of conifers or conserving dead or ageing trees.”

Forestry could be reinvented to include shorter time lines and replace 20-year plans with reviews of management practices every 5 years.

The question arises as to what decisions should be taken when effects are only visible much later? Action already implemented in public forests can only be assessed several decades from now. This is a concern for some managers, who no longer have time to analyse the outcomes of their decisions between two events. Forestry could be reinvented to include shorter time lines and replace 20-year plans with reviews of management practices every 5 years. This adaptive management approach would allow foresters to adjust measures as necessary.

One promising option identified among the factors that determine whether owners change their practices: the possession of a sustainable management document, along with the size of the area owned and the interest shown in one’s forest.

Insuring forests to ensure sustainable forestry

“Insurance is one of the ‘soft’ adaptation strategies recommended by the World Bank.” Marielle Brunette

“Insurance is one of the ‘soft’ adaptation strategies recommended by the World Bank,” explains Marielle Brunette, an economist at BETA research unit in Nancy, “because it helps the owner cover the cost of reforestation in the event of a problem”. Insuring your forest against damage caused by natural events would ensure that a given area remains forest. In France, however, only 5% of forests are insured. The situation is similar in Germany but very different in Nordic countries like Denmark, where almost 50% of private forests are insured. It is unclear whether this low rate is the result of insufficient promotion, an unsuitable offer (only three companies exclusively insure storm and fire risks), or the fact that most privately-owned forests are small (of the 3.5 million private forest owners in France, two million own less than one hectare). Insurance contracts could include clauses to encourage sustainable management practices by “conditioning compensation on management efforts like the use of species mixing, thinning rather than clear-cutting, and shorter harvest cycles in high-risk situations,” concludes Marielle Brunette.

In recent years, the BETA unit has development insurance models for insurers, to address the problem of new risks (drought), dependent risks (drought and fire) and cascading risks (drought and pests). In her thesis 1, Sandrine Bréteau-Amores proposes a new index-based forest insurance model, inspired by the agricultural sector, for the risk of extreme drought. In this model, owners are compensated when the index exceeds a pre-determined threshold.

1. Bréteau-Amores S. 2020. Economic analysis of adaptation options towards drought-induced risk of forest dieback: financial balance and/or carbon balance. Thesis, University of Lorraine.

Payment for environmental and social services

The social or environmental services of private forests can be protected by legislation or by direct payments to owners, via licence schemes or by what is known as payments for ecosystem services (PES). In France and around the world, PES encourage landowners to implement specific measures in their forest to provide one or more services such as water purification, carbon storage for climate regulation, or recreational activities, or to preserve biodiversity. Jens Abildtrup, an economist at the BETA unit in Nancy, gives some examples: “In northern Italy, mushroom fans pay to collect truffles. In Denmark, a licence is required for horseback riding which finances trail maintenance. In Canada, the parking fee is the entrance ticket to the forest.” He adds that “hunters in France already pay a fee to carry out their activities on a private property of a certain size”. “In some cases, this yields results,” says Serge Garcia, an economist at the BETA unit in Nancy. However he warns that to be effective, “the PES must meet certain conditions; payment must be in exchange for a specific action on the part of the owner, for example”, he specifies. In line with the EU Directive on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora, Natura 2000 (see inset below) contracts offer compensatory payment to private or public landowners who commit to protecting biodiversity to a degree beyond what is required by regulation. They are compensated for the loss of income or the additional costs incurred by the silvicultural operation carried out. Only 25% of private forests use this system, however, in comparison to 38% of public forests, likely because payment amounts do not reflect the real costs of the operation, which are sometimes staggered over time.

WHAT IS THE FRENCH NATURA 2000 NETWORK?

In France, the Natura 2000 network aims to ensure the long-term survival of sites in the EU. Each Member State identifies sites and adapts the network’s approach to its own socio-economic context. France encourages landowners (both foresters and farmers) to use environmentally friendly management methods via voluntary contracts that offer compensatory payments.

Encouragement and support

Despite the factors described above and the existence of Natura 2000 for the last 29 years, few private forest owners have committed themselves to this European biodiversity conservation policy. Sometimes the issue lies not in the calculation of costs and payments but a fear on the part of owners that they will lose control over their forest. This encourages stakeholders to look beyond financial compensation and ask what other incentives can be levied to change forestry practices. “Attachment to one’s forest”, replies Marieke Blondet, an anthropologist at the Silva unit in Nancy

And it’s true: an emotional attachment is the top concern of 66% of respondents in surveys2 concerning their expectations and interests with regard to their forests, regardless of forest size or the social profile of the respondents. The production of timber for sale or personal consumption comes only third or fourth for 45% of respondents. “Owners attribute a value to their forest based on their own experience and sometimes that of previous generations, and also on a desire to pass on to descendants a ‘beautiful forest’ as well conserved as possible,” continues Marieke Blondet.

Better identify the many things that drive owners in order to propose a range of incentives.

In addition to these observations, the final report of the AMII project, conducted from 2014 to 2017 and coordinated by F. de Morogue and the FCBA and to which the researcher contributed, highlights the need to better identify the many things that drive owners in order to propose a range of incentives. These could include entrusting contractualisation to forestry professionals (such as the ONF, CNPF or an environmental protection association); the coordination of these organisations upstream aimed at building a range of action that includes sustainable management, certification and biodiversity protection that could be subject to an owner’s commitment, either individually or collectively with these organisations; and the option of ‘redeemable’ contracts that free the heirs of forest owners from any constraints related to forest management. Lastly, creating competitions to reward ‘good forest management’ or the remarkable qualities of a specific forest could lend special meaning to these incentives, like the flowery meadows competition in France which rewards biodiversity-positive management in agriculture.

2. Agreste 2012 (Ministry of Agriculture) and Résofop 2015 (CNPF) surveys.

-

Sarah-Louise Filleux

Author / Translated by Emma Morton