Ressources dossier

Climate change and risksA world of forests

Published on 08 December 2022

Definition: what is a forest exactly?

Definitions vary depending on where the forest is located, the value attributed to it and the goods and services that humans expect from it. The FAO defines a forest as land spanning more than 0.5 hectares (5,000 square metres) with a canopy cover of more than 10%. A tree is defined here as a perennial plant with a single stem (or several if cut back) of a mature height of at least five metres. Foresters use the same three criteria —forest cover, surface area, and species composition of the stand— to estimate and ascertain the current state, evolution and potential of a forest, with reference values that differ between countries and institutions. Forest inventory in France also considers minimum cover width, and excludes anything under 20 metres, such as tree lines. Likewise, forests are on land used exclusively for that and not for agricultural or urban purposes. As a result, tree stands used to produce timber are considered as forests, but orchards and parks are not.

Different characteristics in different forests

Around the world, forests are home to 73,300 species of trees1, each with differing needs and abilities to adapt: some prefer a temperate climate, while others withstand extreme heat or cold or can thrive in unaccommodating soils that lack water or contain salt. Because they determine the structure and functioning of these ecosystems and influence the biodiversity that develops in them, trees are classified as ‘keystone’ species.

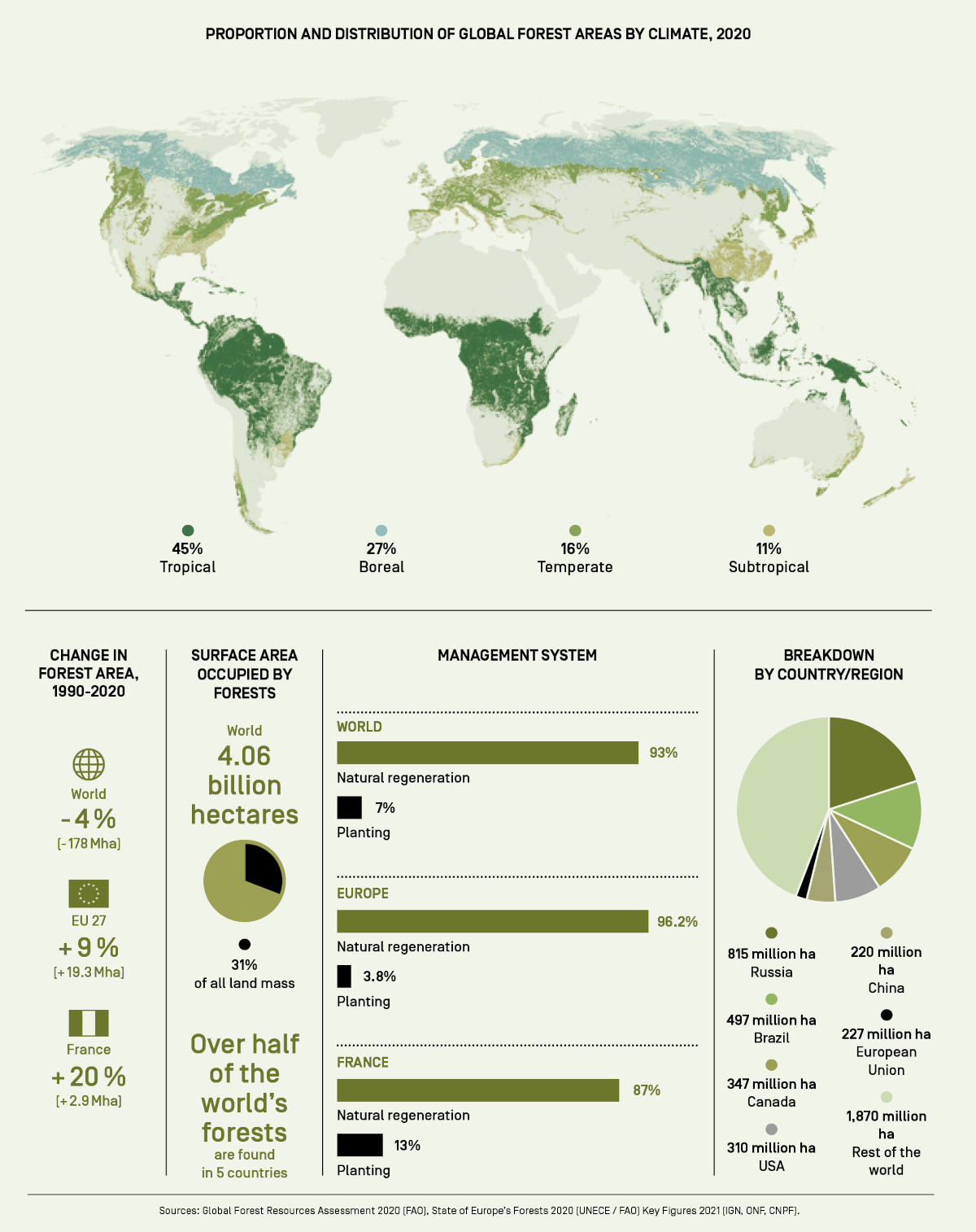

Forest cover2 around the globe is primarily the result of past and present climate conditions that define the five major forest types: boreal, polar, temperate, subtropical and tropical.

Tropical regions receive heavy rainfall during certain periods or throughout the year. Forested landscapes in this region are highly dense and diverse. Examples include the lush cover found in the Amazon (including French Guiana) and South-East Asia, and the drier forests of the Congo Basin.

Subtropical forests, with a warmer climate (22°C minimum average) and contrasted seasons, range significantly, from mangroves to pine forests and savannas, in Mexico, the Mediterranean Basin, the centre of Australia and in southern China and Japan.

The boreal region is populated with mainly coniferous and birch forests, or “taiga”, that withstand harsh winters and temperatures (between –20 °C and –60 °C) and tolerate a contrasted day-length period from season to season. These landscapes are found in Canada, Russia, Scandinavian countries and in France in the Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon archipelago. In polar regions, summer temperatures, below 10°C, are too low to allow for tree growth.

Forests in temperate regions with less extreme temperatures and rainfall levels are populated with deciduous and coniferous trees. Concentrations of certain species are determined by altitude, the presence of waterways, and the nature of forest soils. These forests are more common in the northern hemisphere from North America to Europe, as well as in southern Australia and South America.

1. Recent estimate (Gatti et al. PNAS 2022).

2. Ranking based on FAO's 2020 report : Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020

Human impact

Over time, forest areas in general have been more or less managed and directly or indirectly affected by human activity, making them socio-ecosystems. At times they have been badly damaged by humans in the interest of farming, cities, transportation infrastructure and the activities of a continuously growing population.

World forest cover has diminished by 20% in the space of a century. Deforestation, in which forests are converted into other uses (farming, in particular), has decreased somewhat in the last 30 years. It occurs unevenly: forests in the northern hemisphere are generally expanding, and those in the south are shrinking. It should be pointed out that since 2010, deforestation is more widespread in Africa than in South America.

Planting versus natural regeneration

A “naturally regenerated forest” is one in which canopy coverage grows back independently after a fire or cutting. The FAO estimates that 54% of the world’s forests are subject to a long-term management plan, registered and periodically studied. Practices vary significantly from region to region. 96% of forests in Europe fall into this category, 59% in North America, 24% in Africa and 19% in South America.

One-third of all naturally regenerated cover today is classified as primary forest by the FAO. In this type of forest, human activity has no visible impact on its ecosystem. The European Union considers that 2.2% of its forests fall under this category. Primary forests do not exist in metropolitan France, but a recent study by the LESSEM research unit in Grenoble estimates that 3% of the country’s forests have not been harvested for fifty years or more.

Do forests still act as carbon sinks?

Forests play a vital role in the global climate and help reduce climate change by acting as carbon sinks thanks to photosynthesis and biomass growth like wood.

How much they can store depends on age, health, and, in managed forests, on forestry practices. A forest can emit carbon, for example, following a major environmental issue, such as a heatwave or pests, or overharvesting. Certain forests in the northern hemisphere currently store carbon, while others in certain tropical regions, affected by deforestation or damage, release it. One example is Brazilian forest1 in the last decade (2010–2019), as researchers at INRAE, CEA and the University of Oklahoma have observed.

Forest soils as potential allies

“It should be noted that atmospheric carbon is captured differently depending on the forest, in wood2 and in soil 3 ”, warns biogeochemist Laurent Augusto of the ISPA unit in Bordeaux. “Temperate forests store as much carbon in their trees as in their soils, but tropical forests store more in their trees (56%), and boreal forests store more (60%) in their soils.” A tree’s ability to store carbon changes with age and growth, reaching a peak before it declines. Soils, on the other hand, capture carbon very slowly, over decades and even centuries, and can be valuable allies in the fight against global warming if they are properly managed to prevent human or natural disruptions from rapidly releasing the carbon stored slowly over time. These elements must be factored into sustainable forest management strategies. “ The best way to optimise this role is to carefully select species and silvicultural methods at the compartment and regional level ”, insists Laurent Augusto. The Biomass Carbon Monitor, developed with support from INRAE, monitors changes in atmospheric carbon storage by forests in almost real time. Launched in October 2021, it informs governments, NGOs and professionals on this issue.

1. Qin Y. et al. 2021. Carbon losses from forest degradation exceed those from deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon during 2010-2019, Nature Climate Change.

2. Living biomass (tree, branch, leaf and root). Dead wood is analysed separately.

3. All layers of soil, including the upper decomposing layer (humus).

-

Sarah-Louise Filleux & Catherine Foucaud-Scheunemann

Authors / Translated by Emma Morton