Food, Global Health Reading time 3 min

What are holobionts and why is INRAE interested in them?

Published on 25 June 2020

Holobiont, a strange word to express the "whole of life"!

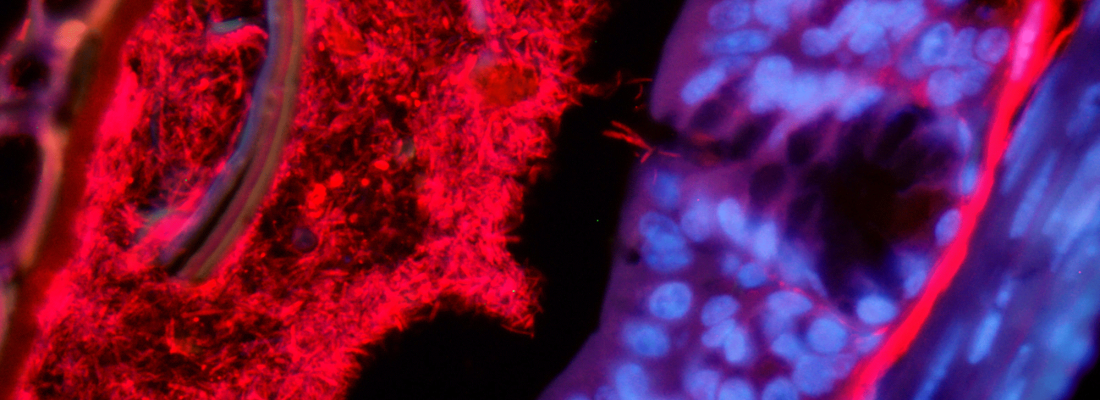

A holobiont is neither a hologram (a 3D photograph) nor a holothuria (sea cucumber)! From the Greek words holos, or ‘’all’’ and bios, ‘’life’’, the term holobiont corresponds to a natural living entity made up of a superior organism (i.e. multicellular) called the host, such as you, me, an animal or a plant, and its microbiota, or the cohort of micro-organisms closely associated with it (bacteria, viruses, archaea, protists and microscopic fungi). In short, it is a host and all its microbes, such as those found in your intestine (around 1 to 2 kg per adult)!

Why and how are holobionts studied?

"The whole is greater than the sum of its parts”, said Aristotle. Although it is sometimes easier to study distinct elements separately, it is also important to study the “whole”, including the environment, because it is not isolated from its “parts”. Studying a host and its associated microbes is a good example. Indeed, the characteristics (or phenotypes) that result from each part are enhanced by those resulting from interactions between the parts and with the environment. This is called the extended phenotype. For example, microbes in the intestine benefit from the nutrients passing through it and produce molecules that have a beneficial effect on the host’s immune system, which in turn will enable it to resist other, pathogenic micro-organisms. Another example is the bacteria present in the roots of legumes which benefit from the sugars produced by the plant and favour its growth by supplying nitrogen. The whole is impacted by other, neighbouring microbes and by the environmental conditions. Taking account of a large number of parameters means that such studies are complex, but adopting a global approach can be of considerable value to understanding how a holobiont functions and then being able to modify, improve or manage it.

Technology to study several billion micro-organisms

This global approach is now possible because science and technology have achieved immense progress in recent years. The human gut microbiota contains around one hundred thousand billion micro-organisms, while a gram of soil contains more than a billion. To study them simultaneously, and to consider their interactions with human, animal or plant cells, it was essential to have access to new genome sequencing techniques and new orders of magnitude regarding the storage, processing and analysis of large datasets (“big data”). Finally, we can now follow microbial fluxes throughout a system; for example, in the food chain from the production of raw materials (crop, harvest) and their processing into a food to their storage, distribution and consumption and the management of waste and by-products.

And within INRAE?

INRAE benefits from a wide range of scientific expertise to work on microbial ecosystems, different holobionts (plants, animals, humans) and different agrifood systems (e.g. wheat, dairy, cattle, agrifood, aquaculture sectors, etc.), and has the essential skills required in bioinformatics, biostatistics and modelling for data analysis.

They study the microbiota of seeds, plants, our gut or the nematode pathobiome. Meet our researchers who study microbes:

> Claudia Bartoli, plant microbiota

> Olivier Berteau, specialist of microbiota biochemistry

> Joël Doré, for the love of microbes

> Harry Sokol, investigator of the role of microbiota in immunity, from patient to cell

In order to mobilise all the cross-disciplinary skills necessary to answer scientific questions on increasingly complex study objects, such as understanding how a holobiont functions, INRAE launched a transversal programme called HOLOFLUX: "Holobiont and microbial flux within agrifood systems” in 2019. Its aim is to obtain a clearer understanding of interactions within holobionts and between microbiotas and hosts on the one hand, and of the fluxes of micro-organisms between holobionts and throughout the agrifood system on the other hand; the overall objective is to be able to control and use holobionts as levers to improve performance and sustainability and preserve human, animal and plant health.

Since 2019, the HOLOFLUX metaprogramme has been funding research projects and PhD grants.

Calls for exploratory projects have enabled a start to the research, on a variety of themes such as:

- Microbial flux from grassland soil to mature cheese;

- The influence of the pig genome on its gut microbiota in order to understand their mutual effects;

- The role of the first bacteria that colonise the intestine just after birth;

- The impact of early weaning in humans and its effects on health;

- The effects of the plant root microbiota on plant breeding;

- The transmission of plant microbiotas to their descendants via seeds;

- The role of the microbiotas of rapeseed and the cabbage root fly in the adaptation of a pest insect to its host.

The funding of four PhD projects will help to better understand:

- The functioning of fermentation in ruminants and its impact on cattle nutrition;

- The role of human intestinal epithelial cells on the balance and imbalance of the gut microbiota;

- The mechanisms that lead to antibiotic resistance and the design of alternatives to antibiotics;

- The impact of competition between microbial species on the microbiota of cruciferous plants.

Projects on a much larger scale and involving international partners are currently under discussion and will focus on monitoring microbial flows throughout the food chain.

Finally, the scientists involved in HOLOFLUX are also contributing to numerous European and global programmes, and notably the MicrobiomeSupport project (https://www.microbiomesupport.eu/the-microbiome-in-the-food-system/) which aims to coordinate and harmonise international research on microbiomes in food systems.