report_type_

AgroecologyEstablishing a new agrifood model

To protect crops from pests, agrifood systems are built from the ground up using synthetic pesticides. Agroecology offers an alternative future. Here's why.

Published on 23 October 2023

There are at least 19 pesticides banned for many years that still occur in the environment.

Protecting crops against natural threats is an essential part of agricultural production. At present, this protection is largely provided by highly effective, easy-to-use synthetic pesticides. Worldwide, pesticide sales increased 20–30 times between the 1960s and 1990s, a period during which food production tripled.

However, the massive use of pesticides and the resulting contamination has had negative impacts on the environment, animal health, and human health. In 2022, INRAE published a joint scientific report declaring that pesticides are everywhere: in soils, the air, and aquatic systems, including the world’s oceans. Coming from agricultural sources, such contamination can result in the loss of biodiversity (e.g., invertebrates, amphibians, soil microfauna) and its associated ecosystem services: pollination, pest control, soil structure, and other soil properties. The environmental omnipresence of pesticides is having significant human health impacts, which are being increasingly recognised. A 2021 INSERM joint scientific report analysed over 5,000 scientific publications and confirmed that a strong link exists between occupational exposure to pesticides and several illnesses, including Parkinson's disease and certain cancers.

Documenting a cause-and-effect relationship is often challenging, which makes it difficult to assess the “hidden costs” of pesticides, including their effects on human health and the environment. A recent study arrived at a broad range of estimates for France in the year 2017. The minimum is €372 million, if we consider the unambiguous impacts of pesticides, a sum that represents more than 10% of the Ministry of Agriculture's 2017 budget. The maximum is €8 billion if indirect impacts are considered, such as the incidence of certain cancers or biodiversity losses.

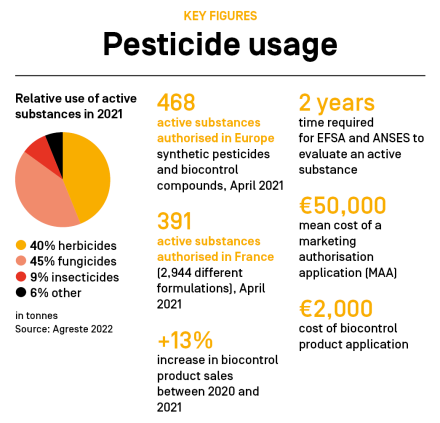

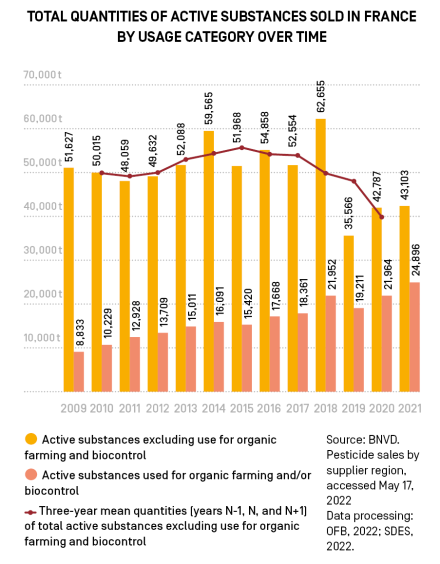

France and Europe have adopted ambitious public policies aiming to better regulate synthetic pesticide use and encourage the development of alternative solutions. Yet, between 2009 and 2018, France witnessed the sale of 51,000 to 63,000 tonnes of pesticides (excluding products used for biocontrol and in organic farming). There has since been a shift. In 2019, pesticide sales began to decline, while those of biocontrol products climbed 2.8 fold between 2009 and 2021. In addition, some of the most dangerous products—those classified as carcinogenic, mutagenic, or toxic for reproduction—were banned (CMR1 substances) or experienced a 57% decline in sales (CMR2 substances) between 2016 and 2020 1. However, this trajectory will not allow us to reach the targets established by the European Green Deal in 2019, which were officially made public in December of the same year by the European Commission. Such remains impossible despite the substantial resources that have been deployed, such as France’s Ecophyto Plans.

1. CRM1 or CRM2 classification based on risk level (certain or likely), EC Regulation No. 1272/2008.

2008-2025 : France’s Ecophyto Plans

France’s first Ecophyto Plan (2008–2015) sought to cut pesticide usage by 50% by 2018. The Ecophyto 2 Plan (2015–2025) pushed this self-imposed deadline forward to 2025. Established in 2018, the Ecophyto 2+ Plan added target dates for phasing out glyphosate. One of the plan’s key measures is the French savings certificates scheme for plant protection products (CEPP). The scheme encourages pesticide suppliers to reduce their sales volumes by marketing alternatives to farmers. These alternatives include resistant crop varieties, biocontrol products, and mechanical weeding equipment.

In return, suppliers receive certificates, whose exact number depends on the resulting estimated reduction in pesticide usage. This figure is determined by an expert commission, chaired by Christian Huyghe, INRAE’s Scientific Director of Agriculture. The plan has made available 120 task sheets and over 3,000 reference products. While CEPP numbers are improving, many suppliers have not yet reached their quotas for 2021: 5.1 million CEPPs have been collected compared with the 16.6 million expected.

A locked-in system

If we are struggling to change current systems despite an already considerable investment, it may be because we are facing sociotechnical “lock-in”. This concept asserts that dominant systems are self-reinforcing as a result of network structures, learning curves, existing standards, and economies of scale. It clearly applies to agricultural systems, which have been organised around pesticide usage. For example, the growth of cash crops leads to intensive farming practices and specialisation on highly profitable species—wheat, rapeseed, and maize—as well as short rotations. The resulting homogeneous conditions favour the occurrence of weeds and pests. Thus, farmers feel that they have no choice but to use pesticides. Attempts have been made to introduce other species into rotations, notably legumes (e.g., lucerne, field pea), but they have been stymied by the difficulty of creating new industries. In turn, seed companies invest few resources in breeding less common species, and equipment manufacturers only construct farm machinery specifically suited to simplified, cash crop systems. Additionally, mass production requires economies of scale, and we are up against society’s idealised vision of farmlands: homogeneous wheat fields completely free of weeds. Lastly, farmers are reticent to give up the simplicity of pesticides for the complexity of systems that will require a substantial investment in the form of time, knowledge, and equipment, which will be accompanied by declining profitability during the transition. On the other end of the supply chain, distributors often impose restrictive criteria, which are the result of high consumer standards (e.g., flawless fruit). It is Jean-Marc Meynard, an agricultural scientist at the INRAE Centre of Versailles, who began disseminating the idea within France that sociotechnical lock-in affects agricultural systems. He also co-authored the 2010 Ecophyto Research & Development Report. To his mind, “the whole system must change if it is to be unlocked”.

Organic farming: leading the way towards pesticide freedom

Organic agriculture emerged in the 1950s and is a system in which no synthetic inputs (fertilisers or pesticides) are used. However, it does employ copper to control bacterial and fungal diseases, including grapevine downy mildew, potato powdery mildew, and apple scab. Unfortunately, high levels of copper can harm plant growth and soil organisms. Indeed, countries such as the Netherlands and Denmark are restricting or even banning its use. Organic farming is thus also affected by efforts to phase out pesticides. INRAE has written a joint scientific report that explores alternatives to copper, notably deploying preventive measures as well as using resistant varieties in tandem with biocides or compounds that naturally stimulate plant defenses. Yet, alternatives are only slowly being adopted, in large part because copper remains widely available.

Limited adoption of biocontrol methods

Biocontrol methods are an essential part of agroecology. While they have largely become the norm in greenhouse farming, their use with cash crops in the field remains limited. In France, sulphur, a natural element, is widely used as a biocontrol product: it helps fight grapevine downy mildew and is gradually being adopted to deal with septoria leaf blotch in bread wheat. In apple orchards, Carpovirusine-based products are frequently used to target the codling moth; in the grape-growing industry, sex pheromones have been effectively deployed against grape worms, albeit over small surface areas (10–15%). Against their invasive counterparts, beneficial insects can serve as effective means of biological control. However, only a third manage to establish themselves, and no more than 10% of those cases result in sufficiently effective control. That said, such efforts have been highly successful when directed against the chestnut gall wasp, a pest originally from China capable of reducing fruit production by up to 80%. INRAE scientists tested the impacts of introducing the chestnut gall wasp’s natural enemy: the parasitoid wasp Torymus sinensis. Next, the parasitoid was widely released in chestnut-growing zones, allowing production to safely resume. This campaign required regional coordination by farmers.

An agroecological transition in food systems

Agroecology strives to minimise the use of synthetic pesticides and fertilisers without banning them entirely. When moderate levels of synthetic nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium fertilisers are employed, agroecological systems are generally more productive than organic farming systems. The European Green Deal has a new vision of agriculture that cannot be achieved without thoroughly revamping our farming systems and diets. This point was emphasised by experts at INRAE and AgroParisTech in response to a report by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). This 2020 publication asserted that the European Green Deal could potentially impact agricultural production, leading to estimated declines of 12% and 7% depending on whether its recommendations were applied within Europe or worldwide, respectively. According to its simulations, food prices and food insecurity would climb across the globe. However, the above estimates were arrived at using current cropping systems. They did not consider possible shifts towards more optimised agroecological systems. For example, INRAE recently took part in an international study that found that when cereals and legumes are grown in association, seed protein levels are higher than when the better-performing crop is grown by itself.

Furthermore, the EU’s Farm to Fork Strategy seeks to bring about a major change: a dietary transformation in Western countries, where people consume fewer calories and animal products and there are lower levels of both post-harvest losses and food waste. The latter is the fate of 20% of Europe’s food. As emphasised in the 2016 Agrimonde Terra foresight study, this shift would improve resource distribution towards the countries of the Global South and would make it possible to feed 9.7 billion people by 2050 without any significant increases in farmlands or pastures. Therefore, there must be systemic change, which involves redesigning agricultural systems at broad scales as well as transforming people’s diets.

Glossary

PESTICIDES

Pesticides are products designed to fight "pests"—undesirable organisms that attack crops.

In this special report, the term essentially refers to crop protection products, insecticides, fungicides, and synthetic herbicides.

PESTS

Any organism that presents a risk to crop health: weeds; pathogenic viruses, bacteria, or fungi; or insects, mites, and nematodes.

WEEDS

Plant species present in agricultural fields that were not intentionally introduced.

PREVENTION

Practices that act upstream to prevent the appearance and spread of pests and diseases.