Agroecology Reading time 6 min

Three questions for a springing sprout: Mycophyto

Published on 23 April 2019

Your start-up is about tapping into the synergy between plants and fungi. How does that work?

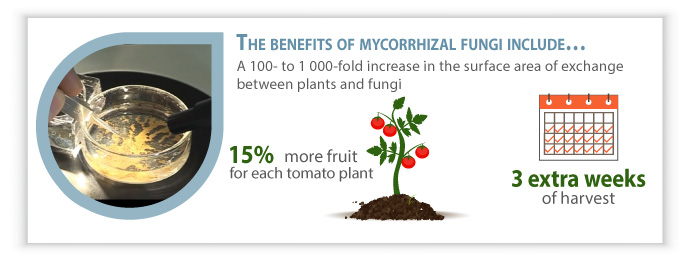

When we resort to inputs like pesticides or fertilizers, we kill fungi. But it’s thanks in part to those very fungi that plants grow! When we use mycorrhizal fungi, we boost the surface area of exchange between plants and fungus by a factor of 100 to 1 000. And if we manage to select the best possible combination, we maximise production by stimulating and protecting the plants. This is how it works: we take a sample of the soil, run analyses (isolation, strains of indigenous mycorrhizal fungi, etc.), then reproduce and multiply the fungi in large quantities. Lastly, we inject them into tomato plants. Since most of the time tomatoes are not grown in the ground, we create models in greenhouses. The result? 15% more fruit for each plant, better nutritional quality, and three extra weeks of harvest!

" Boost the exchange surface between plants and fungi 100- to 1000-fold " |

How did the idea come about and what are your goals?

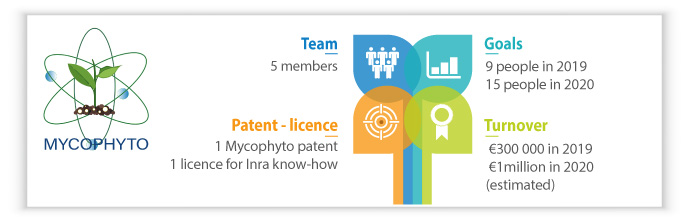

I started running tests in 2017, when I came back from Italy. I continued the following year, as part of a preparatory project at the Université Côte-d’Azur headed by INRA. The project culminated with a technological transfer, and the start-up Mycophyto was born. We started with tomato plants, perfume, aromatic and medicinal plants, and olive trees. Today, we have just about finished raising funds, and have several goals in mind. Firstly, to create jobs by hiring four people by June 2019. Then, we’d like to start re-industrialising, to automate the process for those plants that have been validated for the project. To do so, we are building a strain bank to get new R&D contracts. Lastly, we are forging partnerships to take on new challenges, by combining biotechnologies, Big Data, artificial intelligence, etc., especially so that we can predict what type of fungi will work in which environments. If we are going to make the agricultural transition, I am convinced we need to find not one, but several solutions adapted to different contexts.

"We need to find not one, but several solutions adapted to different contexts" |

Tell us about your work with INRAE

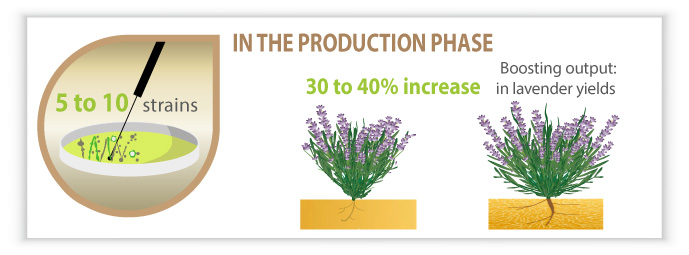

The first steps were taken in Italy, in Turin, with a specialist in plant - microscopic fungi symbiosis. But it’s thanks to INRA that the project was validated on tomatoes. We were also called upon by the University of Grenoble and the European University of Scents and Flavors to carry out a Europe-wide project on lavender to find solutions to counter the plant’s decline. We are also part of the joint technological unit Fiorimed at the Sophia Agrobiotech Institute in Sophia Antipolis. And we’re a spin-off of INRA, with Christine Poncet as our scientific advisor, and benefit from a contract that grants us access to experimental greenhouses, office space, a lab, etc. Currently, we’re talking with other INRA researchers to forge new partnerships, through theses or joint research projects. I am convinced that ties between public research and the end client are crucial: if applied research and the solutions we come up with are to work in real life, we need to continue developing start-ups in tandem with research bodies, and find new ways of working together that are more dynamic and adapted to today’s world! It only makes sense, since working together like this keeps scientific standards high, all the while developing efficient products that are adaptable to the professional world.

After attending an agricultural high school, Justine Lipuma studied microbiology while completing a thesis at INRA in 2015. Her focus was on the interactions between nitrogen-fixing bacteria and legumes (Lipuma J.et al.2015 EMI). In Turin, Julia turned her attention to the symbiosis mechanisms between plants, microscopic fungi and bacteria (Salvioli A., Lipuma J. et al.2017 ISME). Afterwards, she sought to apply her basic research to concrete applications. In the INRA unit of the Sophia Agrobiotech Institute in Sophia Antipolis, Julia met Christine Poncet, who was then working in applied research for designing more sustainable agricultural systems and heading a Fioribio project with Italian partners who demonstrated the importance of the choice of symbiotic partner in optimising mycorrhizal symbiosis. The two decided to create the start-up Mycophyto. “First we conducted interviews to understand growers’ access to products. Those interviews were good for me because I was able to get back into touch with the world of farming, which had not been the case in previous years. The experience taught me that growers are not averse to change, on the contrary! They even lamented an overall lack of support”, Julia explains.

Awards and recognition for Mycophyto |

|---|

|

Since 2016, the start-up has won several prizes:

|

|

|