Food, Global Health Reading time 5 min

Protecting health: a tall task!

Published on 08 December 2020

Each year, more than 43,000 new cases of colon cancer are detected in France. Common in both men and women, it is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths overall. Preventing colon cancer has become an urgent public health issue. Confirming a close link between health and diet, a 2007 report by the World Cancer Research Fund* suspected red meat and processed meats to be the culprit. The “Prevention and Promotion of Carcinogenesis by Food” team (PPCA) of the joint research unit Food Toxicology (Toxalim) of INRAE’s Occitanie-Toulouse centre has been studying the link between colon cancer and red meat intake for more than 25 years and exploring solutions to lower the risk.

Identifying the risk

Heme iron, the team was onto something

While the link between eating meat and related products and the risk of colon cancer has been suspected since the 1990s, health professionals have long wondered which food component is at the root of the problem. Epidemiological hypotheses hold that eating meat and related products increases risk, but fall short of providing proof. In 1997, a team from the French National Veterinary School in Toulouse (ENVT) conducting research on xenobiotics took a closer look at the issue and formulated a hypothesis: could heme iron, particularly concentrated in red meat and processed meats, be to blame? Headed at the time by Denis Corpet, the team joined hands with the Toxalim joint research unit, which specialises in questions related to food toxicology, and together they set out to do some exploring.

Meanwhile, international studies looked at other toxicity hypotheses: protein content, fat content, and cooking method were all called into question, but quickly ruled out. White meat, which tick all of those boxes, is not associated with colorectal cancer. However, it contains almost no heme iron. Without a doubt, the team was onto something. Initial tests on animals confirmed the theory and shed decisive light in the early 2000s: hemin, hemoglobin but also beef and black pudding, rich in heme iron, promote colorectal carcinogenesis in rats.

Once the experimental data is consolidated, science must find a way to go beyond cell and animal testing and extrapolate to humans. There are two solutions: work with humans but in the very short term, with fecal-urinary biomarkers that predict risk, or work with cohorts to study the relation between health and nutrition. “We have a very strong relationship with the team that coordinates NutriNet-Santé”, explains Fabrice Pierre, one of the team’s managers. This cohort of 170,000 “nutrinauts”, monitored individually over time, will allow the researchers to identify, without bias, the circumstances associated with the onset of health issues like colon cancer. Thanks to biomarkers and collaboration with the research centre in human nutrition in Clermont-Auvergne, the team published in 2013 in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition the validation of the role of heme iron in processed meats promoting carcinogenesis in man.

Expertise at the service of public policy makers

But expert findings are not enough; there must be communication and awareness-raising with the general public

From its inception and by the very essence of its research, the team has been involved in public health issues. It provides expertise and is in constant communication with health agencies. Twice, the team has been asked to attend major parliamentary hearings: once regarding ultra-processed foods like processed meats, and a current hearing on the use of nitrites in the sector. Other institutions such as the French National Cancer Institute (INCa) and associations like the French League Against Cancer have done likewise, lending more clout to the group’s research and confirming their impact on society. But expert findings are not enough; there must be communication and awareness-raising with the general public through media campaigns, which are more and more common. “It’s our mission to have a say in the public debate”, explains Fabrice Pierre. “You have to explain the risk without causing undue anxiety, and it’s an opportunity for us to present new data about prevention”.

October 2015 marks a decisive step. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the cancer agency of the World Health Organisation (WHO), classified the intake of processed meats as carcinogenic and red meat as probably carcinogenic for humans. This historic event confirms the research carried out by the team’s researchers since the 1990s. “Denis Corpet was called upon to be part of an expert panel and the WHO relied on other publications the team put out”, explains Françoise Guéraud, deputy manager. The recognition of this public expertise has opened the door to further studies. “It has bolstered our work on prevention” says Fabrice Pierre.

The search for preventive strategies

Research could have come to a halt with this international recognition, but the story doesn’t end there! Scientists are wondering what comes next. How can the risk be reduced in the general population?

Thanks to the support of the Institute and especially that of the Human Nutrition and Food Safety division, the team’s studies showed that heme iron affects carcinogenesis via the oxidation of lipids and its interaction with nitrites. The intake of antioxidants via food would therefore be beneficial. Nutritional recommendations are specific about it: cutting back on red meat and processed meats and/or eating more fruit and vegetables that are rich in antioxidants lowers risk. “These recommendations are clear, but do not reach everyone”, explains Françoise Guéraud.

Food sociologists know what the problem is: while the risks are well-known, that does not stop a good part of consumers from eating too much red meat and processed meats. So, what can be done to avoid the risk of cancer caused by a diet too rich in heme iron and nitrites?

We have to reformulate products that go to market

The team is betting on going back to square one of the food processing chain. “We bring a complementary answer to the table. We have to reformulate products that go to market”, explains Fabrice Pierre. “We are looking for solutions that can be applied in late 2022, by way of specific contracts drawn up between INRAE and the French Pork and Pig Institute (IFIP), and in partnership with 22 manufacturers and their union”. Scientists from the PPCA team, in tandem with researchers from INRAE’s Animal Products Quality unit in Clermont-Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes and Safety and Quality of Products of Plant Origin unit in Avignon, are working with manufacturers to find solutions to change the way food products are made. They are looking at adding antioxidants such as vitamin E or natural extracts that limit the harmful effects of heme iron. These antioxidants, coupled with nitrite alternatives or not, will help lower risk without changing eating habits. Price, look and taste also factor in. To take these criteria into account, the Toulouse team is working in close synergy with researchers from INRAE’s Economics and Social Sciences division, the Centre for Taste and Feeding Behaviour in Dijon, and the French Network for Nutrition and Cancer Research (Nacre). Lastly, thanks to collaboration between researchers from INRAE’s Animal Physiology and Farming division, IFIP, and the company Valorex, scientists can propose new strategies for prevention based on enriching animal feed with antioxidants.

A unique team for a unique issue

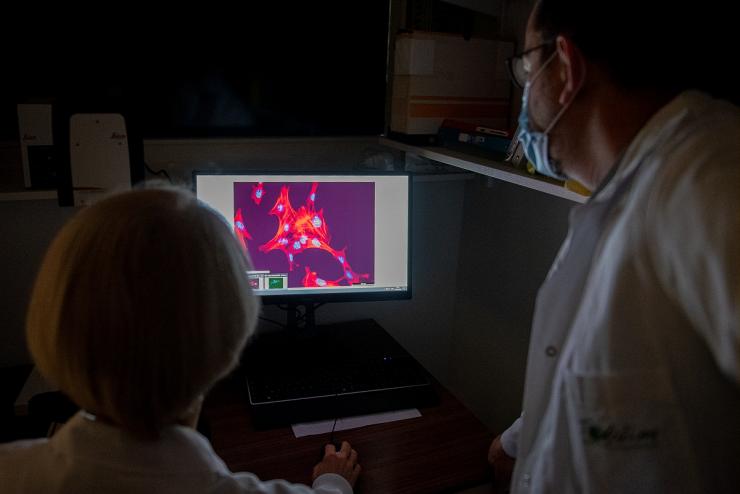

The team benefits from the wide range of skills that its physiologists, biochemists, veterinarians, cell biologists and analytical chemists bring to the table.

They all agree that it is a pleasure to work together to protect people’s health. “I feel useful,” says Nathalie Naud. “And this award recognises the entire team: technicians, engineers and researchers alike!” For Fabrice Pierre, “it’s a source of great pride that this research into cancer be recognised at the level of the Institute.” The “Impact” award is the perfect fit for this team who is re-drawing the map. Thanks to its cross-disciplinary make-up and top-notch skill sets, the team is bringing meaningful solutions for a major public health issue.

Stimulating pairings

Pascale Plaisancié and Jacques Dupuy work at the level of cells and carry out mechanistic studies. Nathalie Naud and Charline Buisson, just like Sylviane Taché at the start of her research, run in vivo studies and put experiment protocols into place. “We are in constant communication with each other,” says Fabrice Pierre. Cécile Héliès and Edwin Fouché connect the dots between mechanistic studies and research carried out on animals, while Nathalie Priymenko brings her expertise on nutrition to the table. In addition to co-leading the team, Françoise Guéraud is a specialist in biomarkers which allows data to be extrapolated to man. Fabrice Pierre maintains communication with cohorts and socio-economic players. And then there are the doctoral candidates, who play a key role in advancing research. Indeed, their job is to explore new possibilities, like Loïc Mervant, who identifies “2.0” biomarkers, or to broaden the scope, like Marie Beslay, who studies the link between psychological stress, eating meat, and cancer.

The award recognises the work of the following people:

Fabrice Pierre, Françoise Guéraud, Denis Corpet, Pascale Plaisancié, Nathalie Priymenko, Cécile Héliès-Toussaint, Laurence Huc, Sylviane Taché, Jacques Dupuy, Maryse Baradat, Edwin Fouché, Charline Buisson, Nathalie Naud, Géraldine Parnaud, Raphaëlle Santarelli, Nadia Bastide, Sabine Dalleau, Océane Martin, Julia Keller, Reggie Surya, Juliana De Olivera Mota, Marie Beslay, Loic Mervant, Claire Maslo, Elodie Tauziet

Team achievements:

ONE risk factor: identification of a main factor responsible for increasing risk: heme iron

ONE goal: limit risk in the general population

ONE nutritional prevention strategy and THREE possible pathways: boost antioxidants in consumer diets, products that go to market, and livestock feed

SIXTEEN team publications used by the WHO’s workgroup to classify the consumption of meat products

FOUR impacts: Output of academic data / Interaction with socio-economic players/ Participation in the public debate / Focus on the debate

1998: first publication on the effects of eating processed meats in animal models

2003: first publication on the identification of factors involved in the effect

2006: first publication on a urinary biomarker

2013: first publication with data for humans (AJCN 2013)

2015: classification by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC-WHO) of processed meat consumption as carcinogenic (class 1)

2019: start of the joint INRAE/meat sector project for implementing prevention strategies within the sector by 2022

2010-2020: parliamentary hearings on (1) ultra-processed foods and (2) nitrites. Interaction with the French League Against Cancer

*WCRF. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington DC: WCRF and American Institute for Cancer Research; 2007. p. 1–537.