Biodiversity Reading time 3 min

How grapevine downy mildew invaded our vineyards: a look back at its voyage from North America

Published on 26 March 2021

There are several vine species, but also several species of the pathogen that cause grapevine downy mildew; each of the latter adapts to its host, thus complicating our understanding of its history and how it arrived in Europe. Downy mildew was first detected in France in 1878, but did one or several species form the bridgehead for its the invasion of Europe?

Tracking downy mildew in Europe

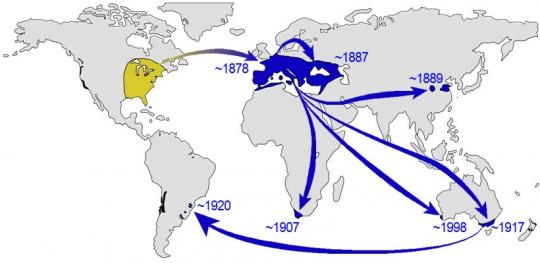

The scientists adopted a multidisciplinary approach to answer these questions, and discovered that the first contamination of European vines occurred 150 years ago and involved a single species of mildew, that which infected the wild vine Vitis aestivalis. The team then tracked it back in order to understand how it managed to infect French vineyards. Their study suggests that the pathogen was introduced via wild American vines that were imported in order to control of powdery mildew and phylloxera1. Because France was the first country to be affected by phylloxera, it intensified varietal innovation by incorporating disease resistance from American wild vines in cultivated vines (V. vinifera). These cultivated European vines then served as the source for the introduction of the disease into vineyards throughout the world.

Starting in the 19th century, France was taken as the model for the modern vineyards that have developed worldwide and thus exported its hybrids and phylloxera-resistant rootstocks, and notably European varieties from the best known regions at that time (Cabernet, Merlot, Chardonnay, Syrah, etc.). It is therefore international trade that acted as a vector for the spread of downy mildew.

This scientific study offers new insights on grapevine downy mildew and notably its spread throughout the world. It highlights the importance of regulating international trade in plant materials in order to prevent other mildew species from being introduced into our vineyards.

|

Reference Fontaine et al., 2021, Current Biology 31, 1–12 May 24, 2021 ª 2021 Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.03.009 |

1 pest that affects commercial vineyards worldwide and which originated from eastern North America.