Society and regional strategies Reading time 4 min

Artificialised land and artificialisation processes: determinants, impacts and levers for action

Published on 08 December 2017

Land artificialisation is now considered as one of the principal factors eroding biodiversity and also a net loss of resources for agriculture and wooded or natural areas. The collective scientific expert report compiled by IFSTTAR and INRA, the results of which were presented and discussed during a symposium on 8 December 2017, showed that efforts to limit land artificialisation must also be accompanied by tools that will reduce its impacts.

A consensus is needed on how to measure artificialisation

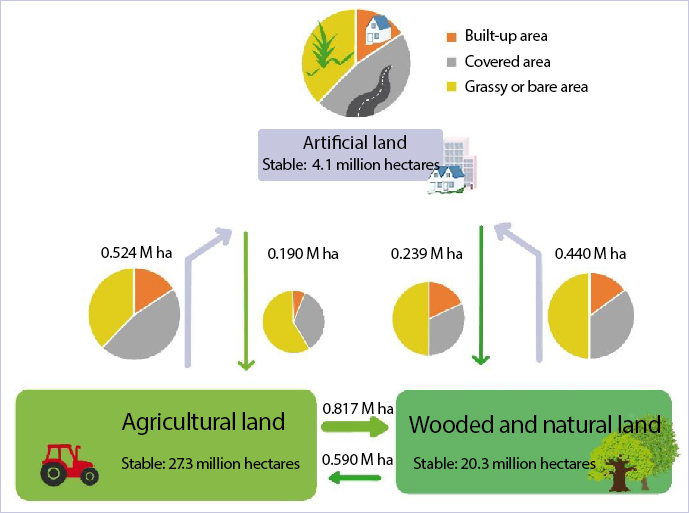

The statistical definition of artificialised land covers all non-agricultural, non-wooded and non-natural land. It thus concerns all surfaces that provide a substrate for human activity (except for agriculture and sylviculture): towns, housing, industry and transport networks. The influence of towns is growing and they are tending to sprawl, with some urban activities extending into the surrounding countryside and thus forming peri-urban areas within which the rate of artificialised land is rising. Nearly half of the land artificialised between 2006 and 2014 was used for housing, by which time the latter concerned more than 40% of all artificialised land. Industrial land use (companies, warehouses, commerce) now covers 30% of artificialised land and has caused a more rapid increase in sealed soils than housing. The same applies for artificialised land used for transport infrastructures, which also account for 30% of artificialised land in France.

Depending on the method used, estimates of total artificialised land in France vary considerably: from 5.6% according to CORINE Land Cover (remote sensing, 2012) to 9.3% from the statistical survey by Teruti-Lucas (2014). The expert report compiled by INRA and IFSTTA suggests that a methodology that crosses remote sensing at its most detailed level with cadastral and topographical data and field surveys in order to confirm land use could improve these measurements. Three types of indicator are necessary to improve the management of artificialisation:

- Disturbances that have affected the soil: coatings, surfacing, etc.

- Type of economic and social space: dense urban development, suburban areas, peri-urban areas (with scattered housing),

- Type of activities: housing (which usually develops on non-artificialized land), service activities (greater risk of artificialisation), industrial activities (higher risk of soil pollution) or transport infrastructures (with impacts in terms of fragmentation).

Artificialisation, urbanisation, soil sealing

Two principal phenomena hide behind the figures: soil sealing (built-up land, roads, carparks, etc.) and urbanisation (which may include planted areas within the urban fabric). A sealed soil is lost and cannot be reversed: both underground and above-ground biodiversity are affected by a loss of natural habitats, the standardisation and contamination of environments and spatial fragmentation. Soil structure is also destroyed. However, these impacts can be attenuated by landscape mosaics made up of gardens or green spaces, the planting of trees and the greening of facades or roofs. Whatever the case, biodiversity is modified: specialist species (which display remarkable biodiversity) disappear in favour of more generalist or even invasive species. Artificialisation also has an impact on hydrology (run-off), the creation of heat islands, air pollution or noise, etc. Enhancing quality of life in towns would improve the attractiveness of urban areas, could limit the spread of artificialised land in peri-urban zones and reduce the impacts of artificialization.

The impacts of land artificialisation on agriculture are moderate in terms of land loss and productive capacities, but are felt very strongly at a local level, notably in peri-urban areas (demand for land, fragmentation of agricultural areas, operational problems).

However, land artificialisation can meet the needs of human societies and satisfy multiple demands for housing, service industries, industrial zones and transport infrastructures. These human activities tend to become concentrated in towns, which will then continue to spread, either by pushing town boundaries or through the random development of centres of human activity which eat into peripheral rural areas.

Levers for action

How is it possible to limit the spread of artificialised land and reduce its impact while meeting every need? The principal levers aim to:

- Limit the extension of artificialised areas,

- Reduce their impacts and hence limit their negative effects,

- Compensate for artificialisation.

The crucial tool is urban planning and territorial development. Fiscal tools such as taxes can also play an important role in the dynamics of land artificialisation.

The densification of towns could constitute a lever to restrict peri-urbanisation resulting from diffuse and scattered urban sprawl, which is a major source of land artificialisation. The rehabilitation of empty spaces or brownfield sites in areas that are already urbanised would be an efficient lever in response to demands for housing or production, and could provide services for surrounding areas.

Fifty-five scientists from different disciplines (environmental sciences, economic and social sciences) contributed to this collective scientific expert report which was based on analysing a corpus of the literature containing more than 2500 references. The expert report was managed jointly by INRAE and IFSTTAR and carried out according to the rules of the National Charter on Expert Reports.