Agroecology Reading time 3 min

Nitrogen: key to going organic

Published on 17 May 2021

Nitrogen is a key ingredient to crop growth and development. Plants get nitrogen from the soil and agricultural yields depend on the element. In conventional agriculture, nitrogen comes from synthetic fertilisers which are banned from organic farming. The supply of nitrogen in organic systems depends essentially on manure from livestock, and, to a lesser extent, the fixation of atmospheric nitrogen in soil carried out by pulse plants. But these two resources are neither infinite nor inexhaustible. Today, organic farming represents about 8% of French agricultural production, and less than 2% globally. Taking organic farming to large-scale levels raises major questions for research: could the development of organic farming be hindered by the availability of nitrogen resources that are compatible with organic requirements? And is this limited availability likely to affect crop yields and global food security?

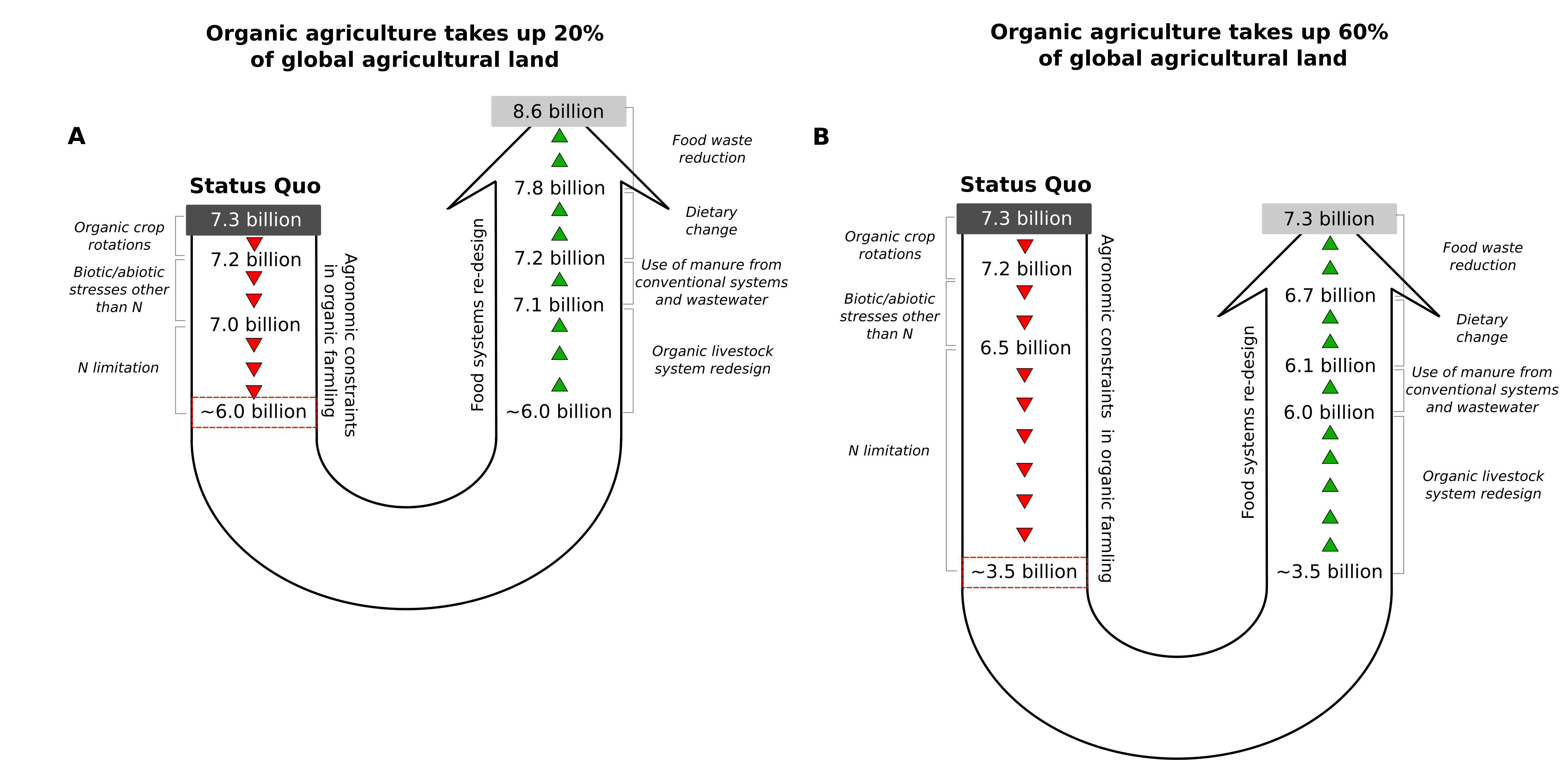

To answer these questions, scientists from INRAE and Bordeaux Sciences Agro developed a model that simulates the supply and demand of nitrogen in cultivated crops according to different scenarios for developing organic farming on a global scale. The scenarios ranged from 20, 30, 40%… even 100% of global cropland going organic. On the basis of current livestock farming practices and dietary trends, their results show that developing organic farming is coupled in many regions of the world with a significant nitrogen deficit and therefore a sharp drop in yields.

Tweak livestock systems and food demand

Livestock rearing is indispensable to developing organic farming because animals produce manure which enriches the soil with nitrogen. But a balance needs to be struck, because animals also need to eat, putting a strain on crops grown to feed humans. That is why a multi-pronged approach is needed, including reducing the overall number of farm animals - especially pigs and poultry, which are in direct competition with human food since they eat mainly cereal crops - and moving grazing animals closer to crops, notably grasslands, to reconnect plant and animal production and optimise nitrogen recycling.

By redressing imbalances in global food intake and by cutting in half food waste at the least, the share of organic cropland around the world could be increased to at least 60%.

Another leverage would be to redress imbalances in global food intake. On average, a person consumes an estimated 2,890 kcal per day, whereas 2,200 kcal would be enough. This re-balancing could be achieved by reducing average food intake in developed countries (now at about 3,000 kcal in Europe and North America) while increasing it in developing countries, notably in Africa. Lastly, food waste would have to be cut in half at the least.

If all these steps were taken, the share of organic cropland around the world could be increased to at least 60% while satisfying global food demand. Experts are currently exploring other ways to develop organic farming such as increasing the cultivation of pulses, which fix atmospheric nitrogen in the soil and could be used to feed both humans and livestock.

|

|

Development of organic farming: effect on agricultural production (in red) and levers that can be activated to support production and meet food demand (in green). The figure shows the number of people who can be fed by agricultural production (organic + conventional) worldwide. The diagram presents two scenarios corresponding to a 20% share of organic cropland (A) and a 60% share (B), the remainder of cropland remaining conventional. © Nature Food |

|

Reference Pietro Barbieri, Sylvain Pellerin, Verena Seufert, Laurence Smith, Navin Ramankutty, Thomas Nesme. Global option space for organic agriculture is delimited by nitrogen availability. Nature Food 2021 DOI : 10.1038/s43016-021-00276-y |