Ressources dossier

AgroecologyThe challenges of expansion

Published on 11 April 2023

Technological developments that have already been tried and tested in other sectors have expanded the opportunities available to agriculture. Our commitment to agroecology as the future for farming has led INRAE to partner with our sister institute for digital research, Inria (French National Research Institute in Digital Sciences and Technology), to ensure that the research priorities of both institutes support the transition from conventional agricultural practices. But something more than the right technical advances will be needed if we are to meet this challenge that encompasses organisational, economic, social and even political transformation. An interdisciplinary approach is required so that the technological solutions we devise can also be subjected to the scrutiny of experts in the human and social sciences. There must be collaboration at every stage of the innovation cycle, creating the process of repeated reinvention that will be necessary for our societies to adapt to continued environmental changes. With government encouragement, researchers, developers and socio-economic actors in France are responding by changing their working practices, engaging with future users of their products and procedures to generate co-constructed and adaptable solutions. Because they are jointly conceived, such solutions are better tailored to the needs of users, who then find it easier to embrace them. It only remains to disseminate such new knowledge and practices to others, being careful to deliver training in a form suited to all generations and farming communities.

Getting the most out of digital for farming

It is no small task to integrate the agroecological and digital transitions. INRAE and Inria have chosen to meet this challenge by strengthening their collaborative activities. As partners on major programmes such as the Agroecology and Digital PEPR (priority research programme and infrastructure) and #DigitAg, the two institutes have together already co-authored more than 400 scientific publications and numerous software programmes and applications. The popular Pl@ntNet application, which has enabled some 20 million users to identify plants using photographs from their smartphones, is just one of their successes.

In June 2022, a new four-year framework agreement set the seal on this shared ambition. It emphasises the necessity of increasing collaboration on digital biology, networked buildings, animal welfare, labour-saving measures, robotics, sensors, the optimisation of networks to access data, and decision-making tools. Importantly, it asserts the need to provide farmers freedom of choice over their use of the digital tools on offer, and the importance of the participatory development of tools that provide genuine support to farmers.

It can sometimes be an immense task to dream up tools able to take account of the full complexity of the systems they are designed to help, and the development of digital twin technology can certainly be described in these terms. Digital twins are extremely detailed digital representations that allow predictions to be made concerning the evolution of a system and that enable users to manage the predicted changes. They have the potential to facilitate and accelerate experimentation by providing a digital replica that resembles the system it is based on as closely as possible. This would allow precious time to be saved in the development process. It will make it possible to test out innovative practices or systems in different configurations and to predict the conditions governing the creation and effectiveness of such innovations, from the conception stage onwards. Because of the speed of the machine-learning processes involved, the results exceed anything that could be produced in a human lifespan. We have not yet determined how digital twins could be developed for agricultural activities, which involve many actors and must adapt to the changes introduced by climate and other hazards. We must also assess their potential for on-farm use as a support for agroecological transition. These are not inconsiderable challenges.

Innovating with participative sciences and partnerships

Participatory science invites all members of civil society to participate in research and to co-construct innovative projects. Apps that allow data to be collected from multiple sources have made it possible for crowdsourcing to increase the potential of research. The GEroNIMO project, for example, collects data from the pork and poultry industries to supplement the information generated by research. Its purpose is to provide farmers with new knowledge and tools that will encourage them to be innovative in their selection of breeds, looking for traits that help animals to cope well with local conditions, while taking environmental issues into account.

For the past decade, the entire French wine industry has been at work on the LACCAVE project, which seeks to share information on the consequences of climate change with the industry and to devise and access different adaptation strategies via modelling. The whole sector’s participation in data provision for this modelling has meant that shared solutions could emerge at both local and national levels (for example the introduction of new grape varieties and novel pruning and grafting practices). The project culminated in the presentation to the French Minister of Agriculture and Food, in August 2021, of a route map for the sector that set out its strategy for adaptation to climate change.

The move from conventional agriculture to agroecology is, however, not without its risks and many farmers consider these to be too great to attempt it. What levers could be found to facilitate transition on a wider scale?

Enriching research with test data provided by farmers

Digital technology is helping to usher in a new era of collaboration between farmers and researchers at all stages of the development process, sharing the benefits of experimentation, evaluation and the capitalisation of knowledge.

As an essential part of the research process, testing has been conducted on experimental farms for centuries. INRAE acts as the scientific lead for many farm networks who are prepared to try out innovative practices with novel tools. Now, digital technology is helping to usher in a new era of collaboration between farmers and researchers at all stages of the development process, sharing the benefits of experimentation, evaluation and the capitalisation of knowledge.

An excellent example of collaborative experimentation in digital farming can be found in Digifermes®, digital farm projects that are mainly run by Agricultural Technology Institutes and Chambers of Agriculture. Each participating farm is supported by a RDI partner that conducts objective and rigorous assessments of the new technologies. Open to digital businesses, start-ups, agricultural groups and businesses, and to all parties who want to help the development of agriculture, “digifarms” are intended to promote a form of digital agriculture that satisfies the needs of farmers. They carry out two types of activity: the assessment under real-world conditions of new technologies and prototypes, and the co-creation and co-construction with end users of digital innovations.

The sharing of testing and data: a necessary step

The farmers collect data as they go about their daily activities, which is then used by the researchers to build models and create scenarios to measure the impacts of jointly-agreed targeted actions. The added value is considerable, but it is not an easy matter to establish these working relationships. OFE (see below) calls for a strong element of trust between those involved, particularly with regard to the protection and equitable sharing of data that may well be sensitive and have potential economic value. In 2021, OFE2021, the first international conference on OFE initiatives, was organised in France, providing a forum for 170 participants from 36 countries to debate these issues. Delegates asserted the need to raise the profile of OFE at public institutional level, highlighting to policy makers the advantages that OFE has to offer for the agroecological transition.

In 2019, the French government instituted its Territoires d’Innovation system. Its local innovation projects are funded by the PIA3 Investments for the Future programme and encourage open innovation at local scale as a means to generate sustainable development models. The area-specific innovation project that INRAE coordinates with partners in the Occitanie Region brings together businesses, start-ups, local councils, chambers of agriculture, competitivity hubs and other players in the world of development, with a focus on farmers and consumers. The goal is to develop innovative digital projects that respond to the particular needs of the participants. Such as, investigating the use of bees as indicators for biodiversity in urban landscapes, finding ways to digitise a survey tool for agroecological infrastructures that currently uses impractical printed forms for its outdoor work, or looking for alternatives to glyphosate to clear the ground in apple orchards.

In their search for answers, the Occitanum partners observe existing practices, send out calls for expressions of interest, encourage dialogue between participants, and support experimentation to identify the best digital options. These options are then evaluated to measure their environmental impacts and check that they have a healthy cost-benefit ratio. Attention is also given to their social implications. The partners verify that both the experiments and solutions meet the three key criteria for upscaling – that they should be documented, repeatable and transferable.

Capitalising on knowledge through training

Once knowledge has been successfully co-produced, information on an innovation must still be transmitted to stakeholders in the sector. Education plays an essential role in this. As part of the “Enseigner à produire autrement” (teaching for a new model of production) initiative, launched in 2014, French students working for the agricultural CAP, Bac Pro and BTS qualifications are now taught about of the challenges of the agroecological transition. As proof of its commitment, the French government’s route map for the development of digital technology in agriculture, published last February, places “digital training in teaching and agricultural consultancy” at the top of the list of 7 workstreams. An early flagship in this field has been the AgroTIC specialism available to agricultural engineering students at Bordeaux Sciences Agro and the Institut Agro Montpellier, which has been providing teaching on digital technology for 25 years. At the Centrale Toulouse Institut-Ensat (previously Toulouse INP-Ensat), a training course specifically designed to provide engineers with dual skills in digital and agroecology is under development. Last, most second-year Masters students at AgroParisTech can now choose a module that will take them “from agronomy to agroecology (AAE)”. These four institutes, like most other French public higher-education establishments and research bodies that are overseen by the Ministry of Agriculture, including INRAE, are members of the Agreenium Alliance. #DigitAg, the Convergence Institute run by INRAE, has forged educational links between its 500 researchers and many actors in research and teaching, including the University of Montpellier, with a hundred or so theses currently being supervised. Meanwhile, Chambers of Agriculture along with training and technical institutes are making digital training courses available to farmers.

A general call for action from government

For an issue as important as food sustainability, the whole of society should be encouraged to act. The ambition to protect this common good has led to a shift in the interface between the public and private spheres, with the emergence of new interactions and dynamics.

Transition calls for the development of major infrastructure and demands substantial investment. Within the agroecological model, with its focus on local management, the power of communities is growing.

Having used its Territoires d’Innovation programme to provide initial impetus to projects in this area, in 2021 the French government pledged a further billion euros of funding for FoodTech and AgTech start-ups. Its declared ambition was to take France from eighth to third place on the global competitivity scoreboard, propelled by the boost this injection of funds would provide to France’s recognised expert activities across the entire food supply network. With global investment in FoodTech and AgTech almost doubling in 2021 and an eye to its ranking, the French government made 200 million euros of support for start-ups immediately available in 2021, with the rest of the promised support being provided through the France 2030 Investment Framework in particular. The allocation of 2 billion euros to Objective 6 of the Framework, “to achieve a healthy, sustainable and traceable food supply”, is intended to encourage the emergence of food champions, to strengthen the development of innovative markets in the food sector and to accelerate the transition to come. Under the plan, new public-private research and innovation structures have been put in place, including PEPRs (priority research programmes and infrastructure) and Major Challenges. Two such programmes, co-led by INRAE, specifically address issues relating to agriculture.

A research programme to foster sobriety and increase the attractiveness of agriculture

With a budget of 65 million euros over 8 years, the Agriculture and Digital PEPR, which is jointly led by INRAE and Inria, aims to federate research from all disciplines at the interface between digital technology and agroecology, and to bring together the relevant socio-economic partners. Its purpose is to direct the development of digital technologies towards products that can support agroecology. To achieve this, it seeks to identify the specific developments that are needed, and to analyse their impacts. Looking at ways to encourage sobriety on the one hand, and to refresh the attractiveness of the agricultural sector on the other.

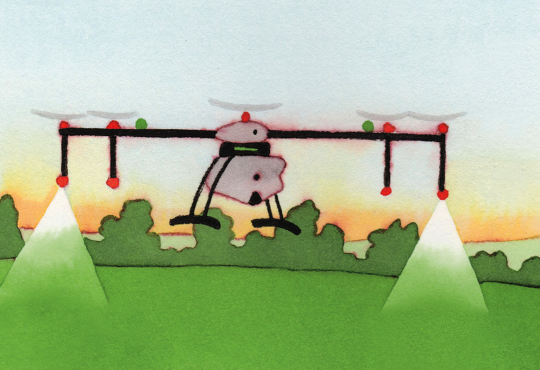

The Great Robotics Challenge

Having achieved a global first with milking robots in 1992, France has lost ground internationally in the development of agricultural equipment. The country has every intention of regaining a firm foothold in a market that was worth 8 billion euros in 20215 and, it is estimated, will be worth 18 million euros in 2025. One contribution to its campaign to win back the markets is the Great Robotics Challenge, which received approval in July 2022 and will run in tandem with the Agroecology and Digital PEPR. Jointly managed by the RobAgri Association and INRAE, it will form a network of researchers, industrialists, competitivity hubs and agricultural federations to shape promising and emerging national work on robotic solutions for agroecology and to accelerate their expansion and development. The network will introduce new practices, develop new technologies, create benchmarked tools and facilitate their use. The Challenge will be based at the Montoldre AgroTechnoPôle in the Allier. It will provide a collective space for multiple stakeholders to learn to debate the issues, work around stubborn obstacles through the use of experimentation, and build a shared vision of the new face of French agriculture.

Building on experimentation on farms

INRAE and the #DigitAg Institute are the French representatives on a team of researchers from France and 8 other countries (Argentina, Australia, Canada, China, Malaysia, Morocco, the United Kingdom and the United States) that has identified six governing principles for this “new generation” of experimentation, referred to as On-Farm Experimentation (OFE) by the research teams involved.

These are:

→ REAL SYSTEMS

Experiments are conducted on farm and are embedded in farm management.

→ FARMER CENTRIC

Experiments are driven by the farmer’s questions and are performed collaboratively involving, as a minimum, both farmer and scientists.

→ EVIDENCE DRIVEN

Experiments are based on the analysis of farm-specific data, which may be facilitated (though not dictated) by digital technologies.

→ SPECIALIST ENABLED

Experiments draw on the contributions of external experts, making it possible for new tools to be introduced and varied viewpoints to be considered.

→ CO-LEARNING

Experiments are built around ongoing discussion between the participants who, in designing and carrying out the experiments jointly, share their visions and experiences, learning from each other and further developing ideas together.

→ SCALABLE

Experiments create knowledge that is valuable locally for individuals, and that is also intended to stimulate broader insights.

The OFE movement includes more than 30,000 farms across the world. Among its participants in France are the 3,000 farms of the DEPHY farm network (created as part of the French Ecophyto Plan), whose members are reducing their pesticide use, and a number of livestock farms whose sustainable systems are monitored by Agricultural Technology Institutes and Chambers of Agriculture. In practice, OFE initiatives take the form of a step-by-step process in which farmers and scientists together define the matters to be addressed, setting up experiments that are tailored to the particular circumstances of a farm.

Welfare innovation: an open-air lab

A majority of the French public has expressed its support for improved farming conditions and practices, attending to the welfare of farm animals from birth to slaughter. To turn this vision into a reality, the LIT Ouesterel livestock innovation laboratory was created in western France. Co-founded by INRAE, Terrena and Triskalia, it builds links between researchers and stakeholders (farmers, the food production industry, consumer groups, members of the public, etc.).

They collaborate in the co-construction, testing and scientific assessment of innovations designed to improve animal welfare. For example, the WAIT4 project, to be launched in January 2023, will spend 5 years testing a suite of automated data-acquisition devices for animals and the farm environment. The project’s purpose is to develop indicators that would enable the welfare of an animal to be assessed throughout its lifespan. Looking in particular at the welfare implications of innovative farming practices, changes in animal feeds, and adaptation to climate change. As part of this project, LIT Ouesterel will pursue an open and participatory science policy, enabling results to be sent to all interested parties. It will also canvas the latter for advice, critiques and suggestions to shape the direction of the research.

The involvement of all partners, in particular that of the general public, plays an essential part in ensuring that the responses brought forward will satisfy public interests and expectations in terms of animal welfare.

A white paper for the future

Declaring a shared mission to “get the most out of digital technology to contribute to the transition to sustainable agriculture and food systems”, INRAE and Inria have set out their research priorities in a white paper. They are:

→ providing digital tools for collective management at a regional level;

→ helping individual farmers to manage their technical journey;

→ transforming relationships between stakeholders within sectors;

→ creating and sharing data and knowledge.

France 2030: Forging an alliance between agriculture and digital

The research and infrastructure projects supported by the Agriculture and Digital PEPR will follow four priority pathways:

→ 1. BUILD a socio-ecosystem that encourages responsible research and innovation;

→ 2. CHARACTERISE available genetic resources to assess their potential use in agroecology;

→ 3. DESIGN the next generations of agricultural equipment;

→ and 4. DEVELOP digital tools and methods for the analysis of agricultural data, the production of agricultural equipment, and decision making.

Its primary aim is thus, through the production of knowledge, to strengthen the range of tools that produce and capitalize on digital data. Its projects could first, for example, seek more rapid and efficient ways to characterise genetic resources in animals and plants, or provide data to model and assess the impact of agroecological practices.

They could then co-produce, with stakeholders from the sector, new generations of digital agricultural equipment to simplify certain agricultural tasks (robotic tools, decision-making software) and to improve animal health and welfare (networked buildings, sensors, etc.).

Last, they could measure the impact of these digital innovations on both the environment and farmers, while studying the contribution that can be made by public policy to such changes in practice and the support it can provide for the farmers who implement them.

-

Aliette Maillard

(Send email)

Author / Translated by Teresa Bridgeman

-

Sophie Nicaud

Author

-

Philippe Fontaine

Author

-

Nicole Ladet

Author